In June Google published its ”AI principles”, the post signed by the CEO himself. It talks about AI sensors for predicting the risk of wildfires. Of farmers using AI to monitor the health of their herds. Of doctors starting to use AI to help diagnose cancer and prevent blindness. Great stuff! We take a look at the context.

As AI is applied to more and more problems through society, it's important to think carefully about the principles by which this is done. We've just shared Google's AI principles, which shows how we've been thinking about these issues. #GoogleAIhttps://t.co/bUomcHKYBz

— Jeff Dean (@JeffDean) June 7, 2018

This tweet, and the article itself, struck a nerve for us because of the way they frame the event. It’s as if senior thought leaders at Google came up with this set of principles (or maybe were given them, like Moses) and now bring enlightenment to the masses.

Quite obviously it is not damage control after the press discovered Google’s interest in AI weapons, specifically about project Maven. The project had to do with analyzing military drone imaging. After much public outcry, the company backed out of the project. As n-gate aptly describes,

Having been shamed into walking away from a lucrative murder automation contract, The Google of Google blogs about how that was totally the plan from the beginning, you guys.

Google’s women, pursuing humanistic AI

Two weeks before The New York Times published How a Pentagon Contract Became an Identity Crisis for Google, our friends at Google posted this:

As technologists, we can build better AIsand better machine learning systemsif we start from the human need. How Googler Fernanda Vigas designs human-centered AI for everyone https://t.co/IOWhrEtV8q pic.twitter.com/fFwYatCpKm

— Google (@Google) May 15, 2018

In our opinion, a great effort to get ahead of the whole Google AI weapons thing. Warm and fuzzy, “human-centered AI”, with a picture of a pretty lady. Old enought to be a mother figure, and still young enough to be attractive. The smile, the hair, the cleavage. Bonus points for her latin heritage. Perfeccin!

The NYT article, on the other hand, opens with a spotlight on Dr Fei-Fei Li, known for her work at Stanford University (she was Andrej Karpathy’s advisor):

She also advised being “super careful” in framing the project, noting that she had been speaking publicly on the theme of “Humanistic A.I.”.

And the quote from her internal email:

Avoid at ALL COSTS any mention or implication of AI. Weaponized AI is probably one of the most sensitized topics of AI if not THE most. This is red meat to the media to find all ways to damage Google.

You know, bad media looking for ways to damage Google! Fake news!

So, on one hand, humanistic AI, on the other, AI weapons. Which image is truer? According to Google Cloud CEO Diane Greene, the motivation to drop Maven was quite simple:

Google would not choose to pursue Maven today because the backlash has been terrible for the company.

In other words, if the whole thing didn’t surface, it would be totally OK to continue taking military money. How’s that for principles. Wait, there’s a word for it: hypocrisy.

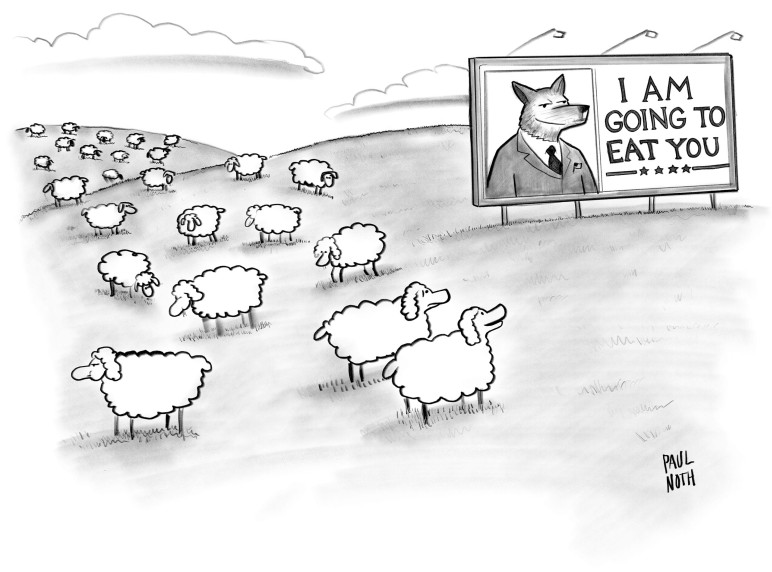

The wolf on ethical treatment of sheep

Once upon a time, Google’s motto was “don’t be evil”. In 2015 they changed it to “do the right thing”. This year, they removed the remnants of the past from their code of conduct:

When Google was reorganized under a new parent company, Alphabet, in 2015, Alphabet assumed a slightly adjusted version of the motto, do the right thing. However, Google retained its original dont be evil language until the past several weeks.

Why change such a nice and simple slogan? Well, at some point the wolf cannot say “I won’t eat you” with a straight face to sheep any longer, because everybody knows for a fact that it eats sheep daily. Therefore, a new meaningless manifesto for ethical treatment of sheep. The wolf is a leader in this field, after all.

Google’s business is mass surveillence. Your email, phone, what you watch (Youtube), where you go (Maps), even what you say in your home - if you pay for the privilege of being listened to - not OK, Google - everything is fair game to maximize advertising income.

The other main player in this game is Facebook. Google has better PR and acts more decisively (2013: military robots financed by DARPA? BUY! 2017: association with creepy military robots? SELL!), so the CEO doesn’t have to constantly apologize and explain. Instead he gets to publish principles.

Lesser fish follow suit. For example, just the other day a guy requested data on him from Spotify and got 850 MB of JSON files:

When pushed with the GDPR, @spotify gives you a huge amount of telemetry data from their app (for me, 850mb of JSON files).

— Michael Veale (@mikarv) June 28, 2018

Includes your A/B testing history, anything you've ever drag-dropped, connected, so on. This is how software works today. pic.twitter.com/mZBRK80NXJ

Presumably, they use it to test those “upgrade to premium” ads to select the most annoying ones, as Spotify rarely display any actual ads for us.

Your browser does “telemetry”, Windows 10 does telemetry, games you play do telemetry. The saddest thing about all this is that it doesn’t seem to improve the quality of anything. It’s madness all the way down.

For more on surveillence capitalism and where machine learning fits in it, read Build a better monster, or some other talk by Maciej Cegowski. They are quite entertaining.

How to log out from a Google account

Long time ago, miners would carry caged canaries down into mine tunnels with them. If dangerous gases such as carbon monoxide collected in the mine, the gases would kill the canary before killing the miners, thus providing a warning to exit the tunnels immediately. [Wiktionary]

Here’s a different kind of a bird, one that lives on toxic gases. As long as it is there, you know the air hasn’t cleared. It appears when you try to log out of a Google account.

There are two aspects of signing in and out of any service. The first, obvious one, deals with access to the service. The second, with the service provider knowing who you are. These may seem pretty much the same, and in the good old days they were, in practice.

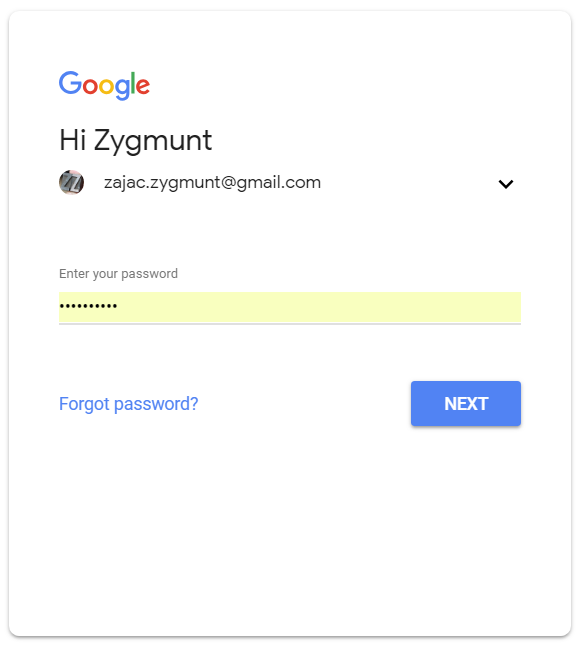

However, somewhere along the road to the brave new world, the watchers came up with a brilliant idea: when you log out, you lose access, but they still see you. To illustrate that, the first screenshot:

Zygmunt clicked “sign out” and now is halfway between logged in and out. The first step was easy, just a click. Now, to log out all the way, one needs to perform a complicated procedure. First, you need to click the small tick on the right. Not the email address, specifically this 24x24 pixels icon. Afterwards, you get to this screen:

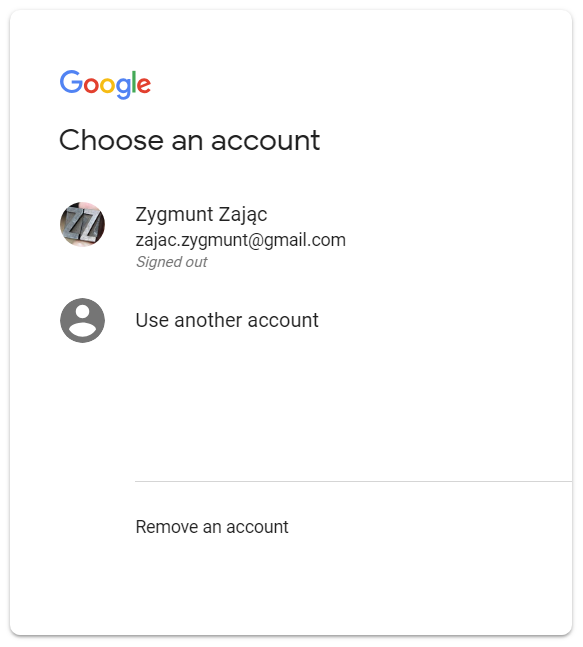

If you stop here, you achieved nothing: refresh the page and you get screen one. Note the “Signed out” line. It’s like a Zen koan: how do you sign out when you’re signed out?

Turns out, one needs to “remove an account”. Good golly, Zygmunt wouldn’t want to remove his account! He may need it in the future. Fortunately, it’s just wording. An honest mistake, probably.

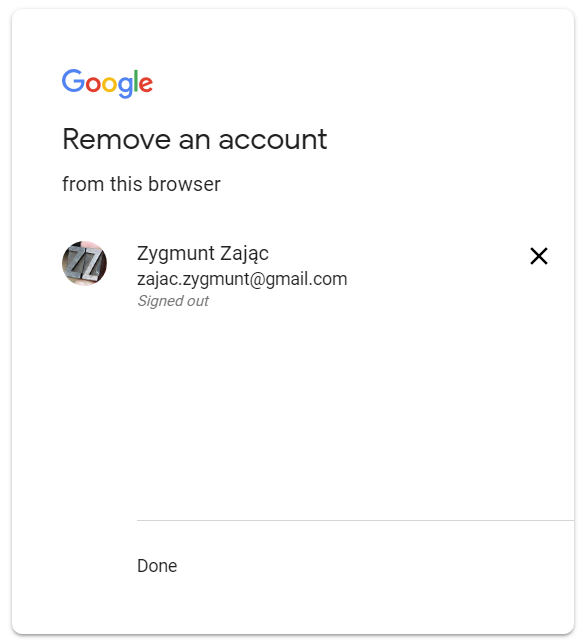

When you muster the courage to “remove an account” after all, you get to “remove an account from this browser”. See? We were just joking, your account is still there.

On this third screen one finally gets to click the cross. Now we’re getting somewhere. Also note the convenient “Done” link at the bottom. Use it to proceed to square one.

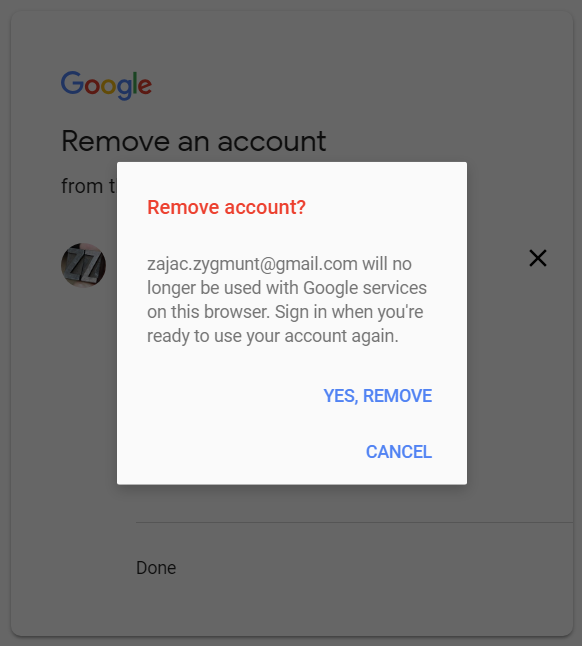

Now this is the final warning, in RED. Fortunately, you are given one last chance to cancel. In case you’re ungrateful and choose “YES, REMOVE”, you’re finally signed out, after mere four additional clicks.

This ridiculous process shows how much Google wants to track you. Don’t believe their “principles” and what they say, just look at what they do. As long as that sequence of screens is there…

2025 update

Google drops pledge not to use AI for weapons or surveillance